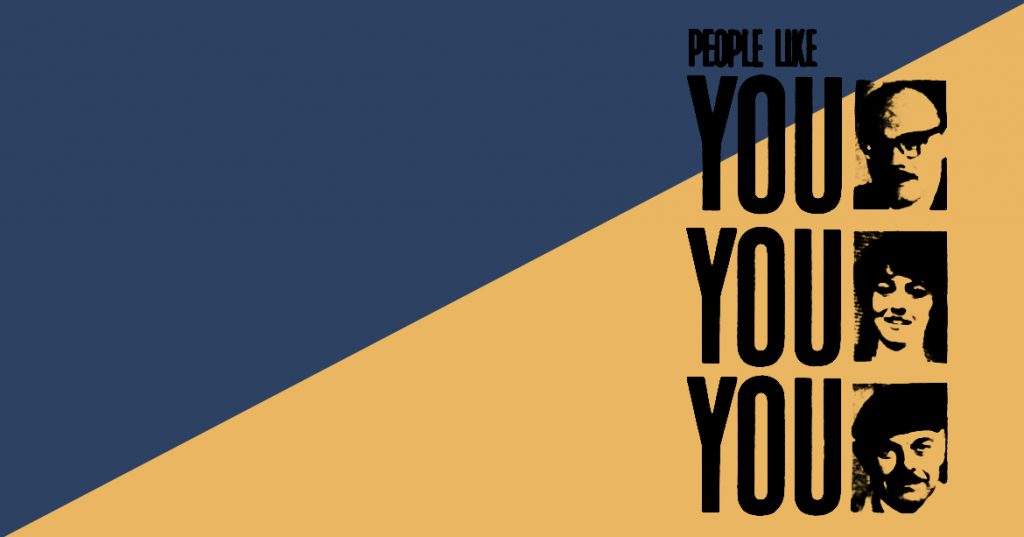

People like you are joining Civil Defence now!

Now’s your chance to join Civil Defence to train to help save lives if ever Britain came under nuclear attack

Days before the official end of World War II in Europe, the coalition government decided to abolish the civil defence structure built up in the run up to and during the Blitz.

Peace was at hand, and civil defence was expensive. Keeping a large payroll of officers and men, plus the physical manifestations in Emergency Water Supplies, Air Raid shelters and First Aid Posts now that there was no longer any threat from Germany was expensive. That money – and so much more – would be needed to fund the reconstruction of our battered islands.

The decision was seen as being proved right when the US ended the war completely in August 1945 by the use of a new ‘superweapon’ – the atomic bombs that were dropped on Japan in an effort to save the 2 or 3 years and 1,000,000 Allied lives it had been thought that a conventional war in mainland Japan would cost.

However, the United States’ atomic bomb project was heavily leaking, and the USSR soon had its hands on the full specifications of ‘Fat Man’, the Nagasaki bomb. Using captured German rocket scientists and their own nuclear physicists, the Soviet Union set out to develop their own superweapon – largely out of fear that the West would use their A-bombs as a threat to keep the Soviets in their place.

On 29 August 1949, the USSR detonated ‘First Lightning’, their recreation of ‘Fat Man’. On 1 September, a US weather plane, which was looking for signs of fallout from Soviet tests, found the atmospheric pollution caused by the explosion. The Western monopoly on nuclear weapons was over. The Cold War had begun in earnest.

The Attlee government reactivated the Civil Defence system. Whilst there was far less infrastructure compared to that of the Second World War, a command structure and wardens would be needed in the event that this new Cold War became a Hot War, as inevitably this would mean a nuclear exchange would take place. Even if it happened in continental Europe, fallout would remain a problem. People would panic. There would be a need for air raid wardens to help keep the peace. There would be pressure on the ambulance services and the fire brigades. Someone would need to take charge. What if London was hit? The Civil Defence system would need to keep the rest of the country running until central control could be reestablished.

Through the 1950s, the Civil Defence system was kept going largely as a reserve. Bring people in, train them, send them back to their lives, ready to be called back up should The Bomb drop.

And then came the Cuban Missile Crisis. In 1961 there had been an armed stand-off between Soviet forces in East Berlin and American, British and French forces in the west of the city. This had exposed how a nuclear war would most likely be triggered by a conventional war, and both types of war would be fought in Europe. Partially as a response, NATO positioned US nuclear missiles in Turkey, as close to the Soviet Union as they could get. Too close.

The USSR responded by sending nuclear missiles to be stationed in Cuba, as close to the United States as they could get. Too close.

Another stand-off happened, lasting almost a fortnight, before both sides quietly withdrew their too close for the other’s comfort weapons. But this stand-off was terrifying, especially to politicians of all stripes. It showed that a nuclear war didn’t have to be started by a conventional one. Instead, one could just happen, with effectively no notice at all.

The Macmillan government started to put a lot of money and time into the Civil Defence system. The telegraph wires and poles strung along the edges of almost all railway lines were hurried buried under the cess at the edge of track. Broadcasting stations, large railway signal boxes, government communications hubs, even council offices, were quickly reinforced against all but a direct hit. Infrastructure started to appear again. Most of all, the appeal went out: if you’re able-bodied, we would like to train you in civil defence and keep you in reserve for when – it didn’t seem like it was if – for when a nuclear war came.

This 1964 advertisement appeals to men and women to join the Civil Defence system, get their training, become part of a unit ready to be activated at any time. The training included first aid, fire fighting, civil disorder and defence-in-depth tactics. It was backed with a campaign that ran on television. There was no expense spared on this vital service.

In 1968, following a sharp devaluation of sterling, the Wilson government started to look for ways to save money. The £20 million a year cost (£346 million in today’s money, allowing for inflation) of the Civil Defence system looked like it was being wasted. The Cold War had gone quiet. The two German states had reached an entente; the Berlin Wall effectively separated not only the people of Berlin but the occupying forces as well; the Vietnam War was distracting the Americans; a war of words with China that was to spill over into a border conflict was distracting the Soviets.

The task of Civil Defence was handed directly to local authorities instead of being decided – and financed – by the Home Office. Each council drew up a local plan and co-ordinated it with their police, fire and ambulance services. The Civil Defence reserves were abolished and the build-up in infrastructure reversed. Should there now be a nuclear war, the government would provide advice and information on how to protect and survive to the people, but everything else was down to your local council to organise.

There was an element of gambling in this – local authorities had often been woefully bad at organising Civil Defence in 1938/9, so it was hoped that the younger members now in most council chambers would be a bit better should it be needed again. There was also the gamble that Civil Defence would actually never be needed – that the massive stockpiles of weapons held by NATO and the Warsaw Pact (and, from 1964, China) meant Mutually Assured Destruction, and therefore those weapons would never be used.

We’re still waiting to find that out.

About the author

Russ J Graham is the editor in chief of the Transdiffusion Broadcasting System